Home » Posts tagged 'Ministry of Justice' (Page 2)

Tag Archives: Ministry of Justice

The IPP sentence: At an Inflection Point?

I have followed the Imprisonment for public protection (IPP) issue for over 10 years and seen how political inertia has stifled any chance of reform. But things are now changing. We are at an inflection point. To learn more, I listened to all episodes of the ‘Trapped: The IPP Scandal’ podcast series.

On 25 July 2023 one of its producers, Melissa Fitzgerald, contacted me and invited me to meet their entire team. This led to conducting an interview with two members, Hank Rossi (Consultant) and Sam Asumadu (Investigative Reporter).

10 minute read.

Faith: To what degree have you noticed how the IPP sentence has emerged as a major issue, and could even be stated as a tragedy within our Criminal Justice System?

Sam: I absolutely agree it’s a tragedy in our criminal justice system. Once you’ve done your original tariff, you’re basically being detained on what you might do rather than what you have done. To me, that’s something for science fiction, not a functional society. Preventative detention should not have had any place in British jurisprudence. The IPP sentence was abolished in 2012 on human rights grounds. Because it wasn’t retrospectively abolished, it’s meant that there’s this legacy and hangover of a particular time in British history, from the New Labour government.

Faith: You spoke with Lord Blunkett, was he dismissive or contrite in any way or genuinely mortified by the suffering caused by not only those given an IPP sentence but their families too. Could he have foreseen how this sentence would be implemented?

Sam: It’s hard to comprehend that this is where we are, over 80 people serving an IPP sentence have died in prison taking their own lives, so many people have been broken by what’s happened. Lord Blunkett has been quite vocal about the IPP, he has been contrite, and he has apologised. He does seem to care about the issue, whether that’s a matter of him thinking about his legacy or if it’s completely genuine, I don’t know. I can’t judge what’s in a man’s heart. However, it doesn’t quite matter how contrite he is because it’s still happened and a lot of lives have been destroyed and are still being destroyed, in my opinion. I think he believes that initially, at least, the judges were over applying the sentence to many people. I think it was just very bad legislation on his part and the Ministry’s part. You have to look at what may go wrong, the worst-case scenarios in legislation, because once it is out, it becomes part of bureaucracy, and into people’s hands. People are fallible, especially when it comes to prisons.

Faith: There were alternatives already. He didn’t need to bring in this new legislation.

Sam: He didn’t, but it did look good at the time. It sounded good as well and it was attractive to the people in the government. Finally, we’ll deal with the underclass.

Faith: How do you get beyond any concerns that you may have that your reporting will fall on deaf ears?

Sam: The series is a permanent record of what is an incredible failure of society. I think the authorities can’t hide from it now. We can send questions to Alex Chalk and Damian Hinds to keep pressure up, making sure they know people are watching. They can’t hide from us.

Faith: We are bombarded with messages from the media, be it on social media or in the newspapers. How do you get an audience to not just listen but act too?

Sam: Ultimately, it’s in their hands. We want people to act. What we’ve done is to highlight stories of people who are campaigning family members. They have little to no resources. Listening to that, I hope it makes people feel incumbent that they can do something themselves to help end this horrific tragedy. This could have happened to their family members too.

Faith: As a professional journalist you have an acute sense of right and wrong and fact from fiction. But has the topic of IPP gripped you because of any reason other than justice v injustice?

Sam: I can’t believe that the state thinks that they can keep on saying it’s “a stain on the British justice”, “stain on the conscience of the British Justice” and not rectify it. The state has a duty to care for prisoners whether they like it or not. Yet people have died and are dying on their watch. And I think that there should be some sort of accountability for that.

Faith: I understand prior to these podcasts, you were involved in a piece of research around IPPs with the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies (CCJS). Can you outline the part you played?

Hank: I funded Zinc Productions and we’ve hired Steve, Melissa, and Samantha to do this work. We’ve worked with quite a lot of the families and friends of IPP’s and with a number of IPP sentenced individuals as well. I started a process with the researchers at the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies (CCJS) in 2020. I approached them, having approached a number of criminal justice reform charities about this issue to fund some research on the possibility of an independent tribunal on IPP. Every time I looked further into this, I got more concerned. I almost, you know, started to become unwell myself, thinking this can’t be real.

One of the processes that I thought might help, was a sort of tribunal inquiry when power cannot hold itself to account because of nefarious activities of those who have it. You can get a group of citizens together and hold your own inquiry. That’s what I thought might be a useful way to look at the problems of IPP. Richard Garside and Roger Grimshaw from CCJS sat around the table with me and we came up with a plan to research the idea for an independent People’s Tribunal on indeterminate detention in the UK. That led to a document I was signing to invest some money in their work to research this idea.

I was sort of feeling like we’d achieved something just by having a conversation when so many people, organisations, and people in power were unwilling to talk about it. Richard and Roger took this seriously at the CCJS and we signed an agreement. The very next day, out of the blue, the government was going to be put under the spotlight by the Justice Select Committee as they launched their inquiry into IPPs.

Faith: Do you believe we live in a punitive society, which has then led to one of the flaws in the IPP sentence as assessing the dangerousness of each offender?

Hank: The short answer is yes. We live in a far too punitive society. I’ve just come across a document published by the Prison Reform Trust in 2003 where the writers are looking at sentence length and they’re worried that they are getting longer. Since then, we’ve gone to this extraordinary place now where a whole life tariff is an everyday thing. I call it the punitive ratchet. We are now learning about the significant harm that prison does to an individual. That’s perhaps what I would say about the punitive concept of prison. The way that we engage with it in the United Kingdom is toxic and has become more and more toxic in the 20 years since the millennium.

Assessing Dangerousness is a complex and very difficult business. You could argue that the assessments tools are inherently problematic because of the nature of prediction. That is a fundamental flaw in the idea of the IPP legislation in the first place to think that there was a system that you could implement to usefully predicts people’s behaviour in the future. And initially the whole process of IPP sentencing circumvented assessment for many. They were just labelled as dangerous based on the offence.

Faith: If you talk about dangerousness, this has changed throughout the sentence.

Hank: This is what annoys me endlessly about the fall back of “Oh, well, this person was a dangerous individual”, no, they weren’t necessarily in many of the cases. There is no evidence to me that people can be predictably relied upon to do the same thing in the future. You can say what a statistical likelihood is but that is nowhere near the same as knowing what someone will do. And we know that from the statistics, less than 1% of people go on to commit a serious further offence when they’ve been out of prison.

Faith: Is the IPP sentence a systemic miscarriage of justice?

Hank: Yes, that’s the best short description of it. Some people would say this is not a miscarriage of justice because that requires an individual to have been completely misrepresented in the process. There’s a researcher who calls these sort of events “errors of justice”. In other words, they are less clear. And there’s truth that these people who committed an offence should be punished by a prison sentence. How long they spend in jail should be part of that process. The idea of indefinite detention, that’s a no no. In international law, we shouldn’t do that.

Faith: With the pressure mounting for Alex Chalk the Secretary of State for Justice to act, how hopeful are you that there will finally be a breakthrough?

Hank: I am hopeful. There is action that people are taking and movement in the system. It’s a systemic problem, and what I know about systems theory is that you might have to take multiple approaches to shift a problem in a system. Unfortunately, when people say, well, how do you fix that? they say, well, you have to go through the legislative body and that’s our parliament. And parliament is a complicated place.

Alex Chalk is in the hot seat right now, and I know he’s really feeling it. There are things he could do tomorrow through LASPO (Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012) to make this go away using executive powers. He’s chosen not to use those at this point. We’ll see if there’s continuing pressure from campaigners and from international bodies. Maybe he will be pushed to do more. But the problem is that under international law, this must be looked at on a case-by-case basis. Well, there’s 3000 people in prison to consider on a case-by-case basis. It’s a nightmare. So, we need some executive action. But I have a feeling that things will happen.

Following on from what Sam was saying, I agree this is the most egregious example of state violence I’ve come across in the UK in my lifetime. I’m over 50 years old. People have been persecuted in a way that I’ve never imagined in this country. The IPP sentence is toxic. It’s extraordinary that the system we have has not been able to rectify that. It leads me to believe that we have a very weak parliamentary democracy. Essentially the power of the executive to keep this going when it should not keep going, is too much. There’s something going wrong within the structure with the roles and the regulations of how parliament and our democracy work.

One thing that I’ve concluded is instrumental perhaps, and was talked about 15 years ago, was the merging of the role of the Lord Chancellor with the role of the Minister of Justice, When that job was boiled down into one, you end up with a problem of separation of powers, I think. And that’s a fundamental problem. So that’s something for us to think about in the future.

Faith: I had lunch recently with Shirley de’Bono where she shared with me her next step in her campaign for IPP prisoners being released, to go to the United Nations in Geneva to have discussions with Dr Alice Edwards, Special Rapporteur on torture. I believe you went along too.

Hank: I’ve been communicating and collaborating with quite a number of different people in different organisations, and I wasn’t expecting to be invited. In the week before a meeting was set up, I was invited to attend in Geneva with Dr. Alice Edwards and Shirley de’Bono and others, and the conversation was about what is going on and what might be done. Shirley presented several cases. I mean, just this is a horror show, isn’t it? You can’t make it up. I’m as worried about this as I have been about anything in my life. I lose sleep over this. And I think that this is an important moment. In Geneva more information was sought by the Special Rapporteur and indications were given that statements will be made in the future that perhaps will certainly shame the United Kingdom’s government on the international stage.

Faith: Do you think the UK government should take any notice of the United Nations, and if so, how much pressure should the United Nations place on the UK government?

Hank: The United Kingdom being a signatory to the Optional Protocol on the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT) is a powerful thing. We’ve agreed to do certain things to honour certain international standards, and we’re not doing that. And the fact that this hasn’t been noticed for a decade is shocking. But going back to the torture problem, the United Nations has clear guidelines on this. We’re breaking many of them.

The United Nations doesn’t have legal or legislative making powers, but it has influence. On 30th of August the United Nations special rapporteur on torture made a statement condemning this situation. I believe they’ve sent a letter to our government and their response will have to have sent in before the 23rd of November, when we should hear what the letter said. We won’t know until then perhaps exactly what’s going on, but it’s all very useful in putting pressure on our government.

Faith: In your opinion, should the UK withdraw its signature from OPCAT because the very existence of an IPP sentence, which we know inflicts psychological harm, and psychological harm is a form of torture, does not align with its agreement to OPCAT?

Hank: I think we need to be part of this. And the whole point of mechanisms where someone can criticise you is useful. In some organisations you create a specific chain of responsibilities and it’s often known as “just culture” where whistleblowing is encouraged, and recriminations are not expected if someone highlights a concern. But in this system, we’ve have had the opposite, that the snuffing out of criticism and the silencing of objections has been part of why this has gone on so long. And that’s got to stop. The National Preventative Mechanism (NPM) has 21 agencies appointed by our government to fulfil the obligations under OPCAT. These agencies have certain powers and they’re not using them properly. Also, the independence of them is questionable. Is it time for a review of the NPM?

Three years ago, I introduced the idea of a people’s tribunal on indefinite detention to the Centre for Crime Justice Studies. We’ve weighed up whether there was any need for a tribunal process, if the Justice Committee made these very strong recommendations that change was needed, of course that’s very positive. But what we’ve found is that the government is not interested, and Parliament seems to have gone along with it. There are indications there’s going to be a bit of noise in Parliament about the Victims and Prisoners Bill. The international community are now waking up like a sleeping giant and the possibility of an independent process to hold government to account and to make a record of the situation is still an idea.

Using Disaster Incubation Theory, we can look at this crisis as an unfolding sequence of events, which was almost predictable. Baron Woolf, former Lord Chief Justice, made comments to Lord Blunkett before IPP legislation was enacted that this was a terrible idea. Blunkett claims not to remember the criticism of it, he went ahead and did it anyway. And look what happened. And you know, people have predicted this crisis.

However, one of the biggest problems of prediction is complexity and you can’t just keep people in prison because you think that something might happen in the future.

Faith: Initially an IPP sentence was to be imposed where a life sentence was inappropriate, so where did it go wrong?

Hank: Indefinite detention induces desperation; this is known from psychological research. Induced desperation is a form of psychological torture. There’s plenty of evidence to show that you don’t need more than a couple of weeks having desperation induced in you by this type of prison sentence to suffer mental health consequences. Suicidal ideation, depression, all of these things we hear about over and over again. It’s extraordinary that more people haven’t managed to take their own lives. So, imagine there’s a system which is inducing you to feel suicidal and then to sort of trap you in a suspended animation forever where you can’t kill yourself because they’ve taken away all of the facility for you to do that, but continue to indefinitely detain you. That is like a horror movie. We talk about the “psychological harms” of this, but it is absolutely punishing.

Faith: How has it got to this point where you’ve got so many people dying on a sentence? How has it been allowed?

Hank: It continues for political reasons. These are essentially political prisoners caught in a situation which is way beyond the norm and the political climate is such that it’s very difficult for someone to do something publicly about it. I suspect change may happen quietly in the near future, there will be moves to influence what happens at the parole board hearing, at the prison gate and what happens in various sorts of quiet corners of the system in order to expedite the release of these people while the international community waves its fist at us.

Faith: Bernadette’s story (Episode 6) highlights the ambiguous criteria for prisoners diagnosed with Offender Personality Disorder (OPD) and once on this pathway they are labelled. Why do you think this diagnosis is used against IPP prisoners rather than to help them?

Hank: This is an enormous abuse of power. What’s happened here is a shocking scandal. That’s why a tribunal process might be quite useful because since the invention of the Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder (DSPD) twenty years ago they were constructing a diagnosis out of thin air for the purposes of managing people in a system, in this case processing them through a criminal justice system. The outcome of that is quite toxic, especially when we know that the incarceration of individuals has severe implications on their behaviour. The National Offender Management Service (NOMS) then implemented the Offender Personality Disorder Pathway (OPD) which might be seen again as a bogus system. It’s invented for management of people who are likely to be disruptive because of the nature of how human beings respond in a prison system.

Research by Robert Sapolsky on neuroendocrinology and research by Daniel Stokols, who is an environmental psychologist, suggests that people in prison systems are very likely to misbehave for many reasons if their circumstances result in a reduction of their agency. If you don’t have a strong identity or a strong sense of purpose, and you are subjected to many of the things that are happening currently in our prison system, you’re very likely to have people starting to suffer mental illness.

Sam: I think most IPP prisoners say I understand my original sentence and the original tariff. It’s what’s happened beyond there I can’t get to grips with and why I’m so distressed by it all. So, I don’t think it’s like shirking responsibility. They do say, okay, fine, I did what I did. Maybe I deserved custodial, but this is beyond what ever should happen to a human being.

Faith: As the OPD Pathway was originally designed for problematic prisoners, do you see any logic in 96% of all IPP’s are given this diagnosis?

Hank: It is cruelty beyond belief. Well, you’re going to be causing trouble if you feel you are being tortured, you’re going to become problematic.

Faith: With Bernadette’s partner, there seems to be little understanding or consideration of how he would struggle when medication for bipolar was withdrawn as a result of a new diagnosis of OPD. Do you see this as a cost-cutting exercise or something else more sinister? Where is the duty of care?

Sam: I think maybe they started with the intentions of cost cutting, this whole sort of merry go round of people being sent to psychiatric hospitals. They thought they could keep it inhouse and that they could label people with personality disorders and keep them inside these NHS units. But then what has happened is that it has become a tool to cage problematic prisoners which people on an IPP sentences will be just because of the nature of what’s happening to them. IPP related distress is not factored in with the OPD pathway, including at parole as we see.

I won’t use the word sinister, but it does feel like it was a way to preventively detain these people. By labelling them as having a personality disorder, or offender personality disorder, which we know is made up.

Faith: The provision of medication or the lack of medication should be a clinical decision and yet it is left to non-clinical staff to determine. Where do you think this failure originates and who is to blame?

Sam: I don’t know the answer to this question. I guess there’s a lot of bureaucracy that comes into this. I think it’s you who said to me that sometimes, prisoners move from prison to prison and their files don’t catch up with them. Then the prison staff don’t even know that they’re supposed to have medication at this time.

Hank: Clinical decisions should be made by doctors. The whole thing with, DSPD and the OPD where clinicians are left out, how can that make sense? Well, one of the reasons is there aren’t enough clinicians working in the system. This prison system creates mental health problems. It’s a double crisis.

Faith: Those in prison should get the same level of health care in prison.

Hank: Well, I have heard some anecdotal stories, some people have said that it’s hard to get mental health support outside prison, they have had better sort of conversations inside prison. It is hit and miss.

Someone who worked in a general hospital told me that the psychology services were downplaying people’s conditions because they knew they couldn’t provide resources to help them. Psychological assessments were being downgraded in the sense that if someone came in and they hadn’t actually tried to commit suicide, but were expressing suicidal thoughts, they were sent home because there was nothing that could be done. That’s extraordinary. That’s just out in the community. And we think the same things happen in prison.

Sam: I really don’t know where to lay the blame on this one. I think in some ways prison governors should have more discretion maybe to help how they deal with their prison.

Faith: In your pursuit of the truth about IPP it appears you have uncovered a further irregularity. In IPP Trapped podcast, Episode 6, Prof Graham Towl, previously Chief Psychologist at Ministry of Justice, says that Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder (DSPD) was invented not by psychologists but by politicians. This is an astounding revelation.

Sam: The DSPD, a precursor to the IPP, was brought in, in the late nineties. The DSPD and eventually IPP was a way to preventively detain people that they didn’t know what to do with whether that was correct in terms of criminal justice or not.

Faith: Is resentencing the only way to ensure that no one spends the rest of their life in prison despite having not been convicted of an offence of gravity that would warrant life imprisonment or is there some other way?

Hank: The government has re-sentenced people before. Resentencing is the thing that works for justice, but it might be slow, and it may not work well for the emergency that I see. I think this is like a mass casualty situation and it is a crisis with significant humanitarian costs, and it needs to be sorted out quickly. You can’t keep torturing people once you know that that’s what you’re doing. There’s a sort of denial going on amongst the authorities. Re-sentencing is a part of the story, but it might be that there are other things in the nearer term that might be needed to expedite certain people’s recovery. But yes, it’s definitely part of the network of considerations.

Faith: In practical terms how hard is it to change IPP? Must it be legislative change or a judicial change, or a policy and practice change? But in the case of legislation to that end takes time, given the prevalence of self-harm and suicides amongst IPP’s, some don’t have that time.

Sam: I think James Daly MP, often says these people could be in prison 40 years down the line. It sounds incredible, but. Yeah. If nothing is done, it could be 40 years.

Faith: I read that 75% of recalls to prison were IPP’s, yet 73% of these recalls didn’t involve a further offence. Do you think the criteria for recall is too broad?

Hank: Absolutely. This is all about risk aversion. For some reason, IPP’s have been put in this network of problems where risk aversion is of the highest order. Essentially the system assumes that they are the most dangerous people on Earth, and they really aren’t.

The parole board is getting it wrong; the probation service is getting it wrong, the judiciary got it wrong, and the government is getting it wrong. I can’t see any point in the system where they’re getting it right. That’s a frightening thing. We can keep talking about it and we can keep hoping that they will change because the more we talk about it, the less likely they’ll get away with it.

Sam: With recall, there’s the human element of probation officers where they just get things wrong, they are overzealous. One story I heard was someone who had moved address, he’d spoken to his probation officer, and he thought it was approved. A week later, the police collected him from his new address, saying that he breached his license, giving the reason as his change of address. But how did they know the address if the probation officer didn’t tell them? This strange logic that seems to be that the first principle is send them back to prison rather than keeping them in the community and finding the best ways that they can work with them.

Faith: With probation as with prison officers so many have left the profession and you’re left with those with very little experience. You are left with a system run by inexperienced people. So, mistakes will happen.

Hank: Along with the punitive ratchet, the problems in probation are the biggest thing that’s happened in the last 20 years. Everyone’s overloaded. And it’s just a system that’s in crisis again. From the moment you’re arrested for an offence, the police are in crisis, the courts are in crisis, the prisons are in crisis, and the probation service is in crisis. This does not bode well for a quick answer to this. I think this topic should be at the front of the queue for fixing and sorting. The discrimination that someone on an IPP is suffering from where a person who’s committed the same offence, who’s in the same cell or next door who’s getting out after a fixed term, that is discriminatory.

Sam: That’s why they talk about violent offenders when they’re talking about IPP and don’t look at the individual cases. Most cases between 2005 and 2008, were not serious crimes.

Hank: The whole thing is bewildering. I hear myself say “I can’t believe this is happening in our country”, especially a country that used to pride itself on having one of the better criminal justice systems. Other countries model their justice systems on the British system, and it turns out we’ve got the most rotten system around.

Faith: The criminal justice system is in such disarray, isn’t it?

Hank: Despite all the independent monitoring that goes on, it’s very hard to imagine that there’s not a lot more going unreported.

Faith: In your opinion is the current Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice, Rt. Hon Alex Chalk KC MP, going fast enough to resolve IPP in his tenure or will he too run out of road before the next General Election is called and purdah prevents any further progress being made.

Hank: I do think that Alex Chalk is listening and we’re getting messages that he’s thinking about what else to do. Then there’s this interaction with the United Nations. And we also know that there are news stories in the pipeline in the next few weeks. The weight of pressure for change on the system is as strong as it’s ever been. The campaigners who’ve done things have done amazing work. MPs are now better informed than perhaps they have been for some time. It is a window of opportunity. It may be that there’s judicial processes that haven’t been thought of because if the United Nations have stated that this is a particular problem, then perhaps there is a legal route that hasn’t been considered before because the United Nations hadn’t made a statement. But now that they have, now that the light is shining on the topic in a way that it hasn’t for a while, I think perhaps, you know, judicial processes might come to bear that haven’t been used before.

Sam: There is also the Victims and Prisoners bill. I’m not sure what happens if a general election comes along, but I think that’s what Sir Bob Neill is counting on if behind the scenes they’re not able to persuade Alex Chalk about re-sentencing.

Hank: It is a good idea. And there’s another amendment proposing an IPP advocacy role for supporting individuals at the parole board and in other ways. But both of those things are slow in coming into force. If there was legislation, it will still take a year. When you’re talking about a few years for anything to come of that, it isn’t very hopeful, is it? We want things to happen now. I think executive action is more likely to solve the problem in the shorter term. But yeah, I fully support everyone doing everything they can in the legislative process.

Thank you for reading to the end of the interview. The topic has engaged you and, hopefully, informed you. But what now – what will you do with what you now know?

There are several things you can do:

1). Write to your MP

Everyone can write to their MP about what you think about IPP sentencing. If you don’t know who your MP is, you can search via the ‘Find You MP’ via this link [ https://members.parliament.uk/members/commons ]. Simply put in your postcode and the page will give you their name and contact details.

2). Social media

If you use a social media platform you can share your thoughts about the IPP sentence. If you want some ideas, you can share a link to the ‘Trapped’ podcast series, or share a link to this blog interview. Or both.

3). Support a campaigning group

You can find a group which campaigns for change in the IPP sentence. There are several. Why not start with the one called UNGRIPP. Their website is www.ungripp.com They are on Facebook and on X, formerly Twitter.

4). Above all, please don’t do nothing.

Prisons make more problems than they solve

Recently I watched again the movie ‘Erin Brockovich’ about a woman determined to get justice. My brain became filled with questions but instead of going to bed I decided to write and to capture what was in my head.

How many times will I have to read reports from the IMB, from the Inspectorate, from the PPO, all saying the same thing year after year?

How many more times will I have to read about the misery in prisons, the terrible food, the conditions that prisoners live in?

How much longer will I have to read about self-harm, deaths in custody, suicides and not just of prisoners?

How many more campaigns will I read about from organisations trying to better the system, yet very little ever changes?

Are there too many individuals and organisations wrapped up in “Prison works” and patting those on the back who are “heroes” or something. Meanwhile, watching this space carefully, it appears to me that senior members of HMPPS are beginning to jump ship.

Ministers come and ministers go but, looking at reality, I wonder what they are actually doing to bring to an end the misery and violence within our prisons. Yes, I say our prisons because our taxes pays for them. It’s like pouring money into a black hole.

Oh, and what about Rehabilitation?

What about Education?

Yet still we build more warehouses and more warehouses that don’t work, have never worked and I doubt will ever work in the future. And for what reason? Just this week the new Five Wells prison has come under scrutiny, missing the mark in many areas already just a year after it officially opened. Shortages of food, availability of drugs, turnover of staff, all this causing deficiencies reasoned away simply as “…considerable challenges that come with opening a new prison”.

We read about other prisons where those imprisoned for sexual offences have not had the opportunity to address their issues and their crimes are released back into society, homeless. Others who were given an IPP sentence languishing in their cells, not knowing when or if they will even be released. And also those imprisoned under joint enterprise.

We are making more problems, not solving them.

Despite what some people say, In the last 5 years I have visited many prisons. For example, I have delivered training to Custodial Managers and Prison Governors (Wandsworth), twice eaten at a restaurant in a prison (Brixton-Clink), attended an art exhibition in my local prison (Writer in Residence, Warren Hill), observed courses (Chrysalis, Oakwood), celebrated with prisoners on completion of their courses (Stand-Out, Wandsworth) and many more opportunities to talk with Governors. I have seen for myself some of the issues facing staff and prisoners.

Surely there is a better way.

If all we can do is build more prisons.

Prisons boast “we have in-cell technology” as though it’s like something from another planet.

Prisons boast “we have in-cell sanitation” as though it’s a gift when this should be standard.

Almost a year ago a Judge told me that even though they sentence people to custodial sentences, they had never set foot in a prison themselves. I sent a quick message there and then to put them in contact with someone I knew who could help change that.

Prison should be the last resort, and only for those that are a danger to society. Yet, there are people in prison who are there because it is deemed a safe place.

Prisons are not safe, not for prisoners and not for staff. If you don’t believe me then please do some research.

Overworked, underpaid and inexperienced staff working in difficult conditions.

Conditions deteriorate whilst the population increases.

In August 2019, I accepted an invitation from Rory Geoghegan to a speech on ‘Reducing Violent Crime’ hosted by the Centre for Social Justice. Rory gave me a copy of a paper he had co-authored with Ian Acheson called ‘Control, Order, Hope: A manifesto for prison safety and reform’, three things which in my opinion are severely lacking in our prisons. Rory had contacted me the previous September for my view on a key recommendation concerning IMB’s for this paper, as you can imagine I was pleased to read:

“Independent Monitoring Boards (IMBs) have a role to play, to “monitor the day-to-day life in their local prison or removal centre and ensure that proper standards of care and decency are maintained. In the wake of utterly unacceptable conditions across so many of our prisons, there must be questions about how effective IMB’s have been at ensuring standards of safety and decency have been met.”

Recommendation 59: Government to consult on the role and effectiveness of Independent Monitoring Boards (IMBs) to help ensure that they can play their vital role within the wider system of prison governance, early-warning, and accountability.

Source: page 64 and 65 https://www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk/library/control-order-hope-a-manifesto-for-prison-safety-and-reform

As you can see here, and elsewhere in The Criminal Justice Blog, I have been consistently calling this out for years. The IMB has never been able to ensure anything; if it had then it has completely failed in its remit, as evidenced by the decline in the state of prisons in England and Wales.

Now the prison estate is running out of space, police station cells are on standby, not-so-temporary prison accommodation is being installed as ‘rapid deployment cells’.

Yet still we fill them.

What on earth are we doing?

When will a Secretary of State for Justice make a stand, be decisive and finally bring some control, order and hope into our prisons?

~

The watering down of prison scrutiny bodies

I want to concentrate on two scrutiny bodies: His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP) and the Independent Monitoring Boards (IMB).

It appears that both have changed their remit to compensate for the ineffectiveness of their scrutiny. Are they trying to improve something, or are they trying to hide something?

Does the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) want these bodies to obfuscate the facts of the state of prisons? The dilution of scrutiny results in degradation of conditions for your loved ones in prison, staff and inmates alike, both in the same boat.

His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP)

Website https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/

HMIP inspections have routinely issued recommendations to prisons where failure in certain areas needed to be addressed and in cases where it is possible for issues to be rectified or improved. Applying the healthy prison test, prisons are rated on the outcomes for the four categories below:

- Safety

- Care

- Purposeful activity

- Resettlement

Since 2017, if the state of a prison is of particular concern an Urgent Notification (UN) has been issued. This gives the Secretary of State 28 calendar days to publicly respond to the Urgent Notification and to the concerns raised in it. There have been twelve Urgent Notifications issued so far, and the details from the latest urgent notification for HMYOI Cookham Wood, for example, is uncomfortable reading:

“Complete breakdown of behaviour management”

“Solitary confinement of children had become normalised”

“The leadership team lacked cohesion and had failed to drive up standards”

“Evidence of the acceptance of low standards was widespread”

“Education, skills and work provision had declined and was inadequate in all areas”

“450 staff were currently employed at Cookham Wood. The fact that such rich resources were delivering this unacceptable service for 77 children indicated that much of it was currently wasted, underused or in need of reorganisation to improve outcomes at the site.”

Source: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2023/04/HMYOI-Cookham-Wood-Urgent-Notification-1.pdf

However, the Inspectorate now have a new system where recommendations have been replaced by 15 key concerns, of these 15, there will be a maximum of 6 priorities. On their website it states:

“We are advised that “change aims to encourage leaders to act on inspection reports in a way which generates real improvements in outcomes for those detained…”

Source: https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/about-our-inspections/reporting-inspection-findings/

One of my concerns is whether this change will act as a pretext to unresolved issues being formally swept under the carpet. A further concern is what was seen as a problem previously will now be accepted as the norm. As a consequence how will the public be able to get a true and full picture of the state of the prisons?

Will there be a reduction in Urgent Notifications?

I think not.

Or will the issuing of urgent notifications be the only way to get the Secretary of State for Justice to listen and act? In my view, issues that would previously have been flagged up during an inspection are more likely to disappear into the abyss along with all past recommendations which have been left and ignored.

Could it be said that this change of reporting is a watering down of inspection scrutiny that you expect of the Inspectorate?

Before you answer that, let’s look at the IMB.

Independent Monitoring Board (IMB)

Website: https://imb.org.uk/

Until very recently, the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) website stated that for members: “Their role is to monitor the day-to-day life in their local prison or removal centre and ensure that proper standards of care and decency are maintained.”

But looking at the IMB website today I have noticed that they have changed their role. Instead, it now states that members: “They report on whether the individuals held there are being treated fairly and humanely and whether prisoners are being given the support they need to turn their lives around.”

Contrast that with what the Government website http://www.gov.uk displays, where you will find two more alternatives to what the IMB do:

- 1st. “Independent Monitoring Boards (IMBs) monitor the treatment received by those detained in custody to confirm it is fair, just and humane, by observing the compliance with relevant rules and standards of decency.”

Source: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/independent-monitoring-boards-of-prisons-immigration-removal-centres-and-short-term-holding-rooms

The first is a large remit for volunteers as there are rather a lot of rules to be aware of. I’m sure the IMB training is unable to cover them all, so how can members be required to know if the prison is compliant or not.

- 2nd. “Independent Monitoring Boards check the day-to-day standards of prisons – each prison has one associated with it. You don’t need specific qualifications and you get trained.”

Source: https://www.gov.uk/volunteer-to-check-standards-in-prison

This checking comes across as a mere tick box exercise, which it certainly should not be. Again, I question whether IMB members training is sufficient. What they say and what actually happens is another example of the absence of ‘joined-up’ government.

In point of fact, the IMB has never been able to ensure anything; if it had then they have completely failed in their remit, as evidenced by the decline in the state of prisons in England and Wales. Clarifying their role is an important change, and one I have been calling out the IMB on for years.

Could it be said that this change of wording is a watering down of monitoring scrutiny you can expect of IMB members?

To help you answer that, you may also need to consider the following:

Although the IMB has become a little more visible, I still have to question their sincerity whether they are the eyes and ears in the prisons of society, of the Justice Secretary, or of anyone else?

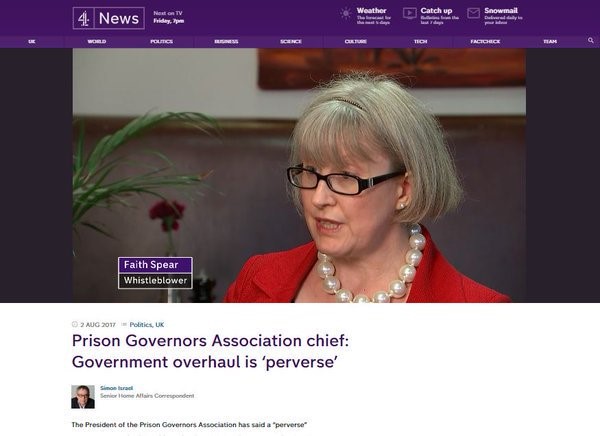

The new strapline adopted by IMB says: “Our eyes on the inside, a voice on the outside.” Admirable ambition, and yet compare that with the lived reality, for example, of my being the eyes on the inside and a voice on the outside, which was exactly the reason why, in 2016, I was targeted in a revolt by the IMB I chaired, suspended by the then Prisons Minister Andrew Selous MP. For being the eyes on the inside and a voice on the outside I was subjected to two investigations by Ministry of Justice civil servants (at the taxpayer’s expense), called to a disciplinary hearing at MoJ headquarters 102 Petty France, then dismissed and banned from the IMB for five years from January 2017 by the then Prisons Minister, Sam Gyimah MP.

If the prisons inspectorate have one sure-fire way of attracting the attention of the Secretary of State for Justice in the form of an Urgent Notification, then why doesn’t the IMB have one too? Surely the IMB ought to be more aware of issues whilst monitoring as they are present each month, and in some cases each week, in prisons. Their board members work on a rota basis. Or should at least.

And then of course there is still the persistent conundrum that these two scrutiny bodies are operationally and functionally dependent on – not independent of – the Ministry of Justice, which makes me question how they comply with this country’s obligation to United Nations, to the UK National Preventative Mechanism (NPM) and Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel Inhuman of Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT), which require members to be operationally and functionally independent.

In 2020, I wrote: “When you look long enough at failure rate of recommendations, you realise that the consequences of inaction have been dire. And will continue to worsen whilst we have nothing more compelling at our disposal than writing recommendations or making recommendations.”

and: “Recommendations have their place but there needs to be something else, something with teeth, something with gravitas way beyond a mere recommendation.”

As a prisons commentator I will watch and wait to see if the apparent watering down of both of these organisations will have a positive or detrimental effect on those who work in our prison environments and on those who are incarcerated by the prison system.

As Elisabeth Davies, the new National Chair of the Independent Monitoring Boards, takes up her role from 1st July 2023 for an initial term of three years, I hope that the IMB will find ways to no longer be described as “the old folk that are part of the MoJ” and stand up to fulfil the claim made in their new strapline: “Our eyes on the inside, a voice on the outside”.

And drop the misleading title “Independent.”

~

Photo: Pexels / Jill Burrow. Creative Commons

~

Penitence versus Redemption in the Criminal Justice System: Unedited

I once entered a cell of a high-profile prisoner; his crime had been blazoned on every national newspaper and was serving the last few months of his sentence as an education orderly. He sat on his raised bed, his legs dangling over the menial storage where he had meticulously and precisely arranged his pairs of trainers and invited me to sit on the only chair in the cell. During our 20-minute conversation, he was pensive and reflective, looking down all the while, except for when he raised his head, adjusted his glasses, then looked me straight in the eye.

“Don’t count the days, but make every day count,” he said, his voice monotone and hushed. Yet behind him, I noticed a calendar marked with neatly drawn crosses. He was clearly counting down his days, paying his penitence until his eventual release from prison.

As an independent criminologist, I have met many who feel a deep-seated obligation to “pay back” continuously in some way to society or a higher power. Those who are caught and convicted for committing a crime experience punishment in some form or other, but when should that punishment end? Is it once a sentence has been served or longer?

Over the last 12 years, I have visited every category of prison in England and Wales and monitored a Category D prison for four years. In all that time, I have encountered hundreds of inmates, many struggling with the punishment, not only that of the sentence given by the courts, but the continual punishment they experience as they serve it, as well as after release and beyond.

The Ministry of Justice proudly states on their website that their responsibility is to ensure that sentences are served, and offenders are encouraged to turn their lives around and become law-abiding citizens. Apparently, the Ministry has a vision of delivering a world-class justice system that works for everyone in society, and one of four of their strategic priorities is having a prison and probation service that reforms offenders.

But I am not at all convinced by this hyperbole. In my opinion, we must stop the madness of believing that we can change people and their behaviour by banging them up in warehouse conditions with little to do, not enough to eat, and sanitation from a previous century.

Penitence

If true reform is supposed to be achieved through time served, then a former inmate emerging from prison with a clean slate would be ready to contribute fully to society. Yet beyond prison gates people who have served their time all too often live under a cloud of penitence, suppressing a sense of guilt for their deeds.

Many of the formerly incarcerated insist on a daily act of penitence, a good deed, even raising money for a worthy cause. For onlookers, such acts carry an air of respectability, but it is important to understand what is really happening on the inside because some of those who engage in them do so as a form of self-punishment. The punishing of self both physically and mentally.

They sense they must compensate.

Their account never fully paid.

Lifelong indebtedness.

And of course there are those who appear to genuflect to the Ministry of Justice and the Criminal Justice System; a sign of respect or an act of worship to those always in a superior position.

On the balance of probabilities, it is more likely than not that some penal reform organisations and some individuals with lived experience approach the Ministry of Justice with such reverence showing their cursory act of respect.

The same act of penitence or faux reverence ingrained into them whilst they served their custodial sentence.

For others penitence is an act devoid of meaning or performed without knowledge.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the definition of penitence is “the action of feeling or showing sorrow and regret for having done wrong, repentance, a public display of penitence.” In addition to the formal punishment they endure, many prisoners engage in penitence both physically and mentally during and after serving their time, which keeps them from moving forward with their lives and is damaging to their sanity.

According to a 2021 report by the Centre for Mental Health, (page 24) “former prisoners…had significantly greater current mental health problems across the full spectrum of mental health diagnosis than the general public, alongside greater suicide risk, typically multiple mental health problems including dual diagnosis, and also lower verbal IQ…and greater current social problems.”

In my work, I have found that some people who have broken the law want others to know that they are sorry, whilst at the same time feel the pressure to prove this to themselves. In such cases, their penitence becomes a public display for families, caseworkers, and those in authority.

Witnesses to this display of penitence often think these people are a good example of someone who has turned their life around, but often, these former prisoners find themselves stuck in the act of penitence. Rather than turning their lives around, they are trapped forever in their guilt. In these cases, the act of atoning becomes all-consuming, an insatiable appetite to heed the voices in their soul that tell them, “you must do more and more, it’s not enough, I’m hungry.”

Redemption

When I speak to those who are serving a whole-life tariff, I know that their debt to society can never be repaid: they are resigned to a lifelong burden of irredeemable indebtedness. But many of those who are released from prison remain incarcerated by their own guilt, feeling as if they must hide any hint of happiness they may find in life after prison so as not to be judged.

For example, in 2019, I interviewed Erwin James, author, Guardian columnist and convicted murderer, who had just come out with his third book, Redeemable: a Memoir of Darkness and Hope. When I asked him, “What makes you happy?” he replied: “In the public, if I am laughing, I feel awful because there are people grieving because of me. Even in jail, I was scared to laugh sometimes because it looked like I didn’t care about anything.”

Just like I saw with the prisoner sat on his bed, I have witnessed a cloud hanging over many, especially when redemption, or the act of repaying the value of something lost, relates to acceptance and society’s opinion of you.

There are of course prisoners who have the intellectual capacity to learn from their mistakes, have the emotional capacity to adapt to their situations and – not forgetting – the spiritual capacity, a dimension that can lead to a voyage of self-discovery. But by no means all.

Unfortunately, in the UK, paying back to society can either be the light at the end of the tunnel, or a tunnel with no light.

I believe we live in a punitive society in which the continual punishment of those who have offended is tacitly endorsed. In so doing, society inadvertently encourages the penitentiaries of this world to hold offenders in an ever-tightening grip.

Even a sentence served in the community—a sentencing option all too often shunned by magistrates—can carry an arduous stigma. In a public show of humiliation, the words “Community Payback” are garishly emblasoned on the offenders’ brightly-coloured outerwear, announcing their status as a wrongdoer to all who see them. Basically, this is society’s way of saying, “we want you to be sorry, we want you to show you are sorry and we will not let you forget it.”

Statements such as “the loss of liberty is the punishment” become fictitious, enabling punishment in its various form to continue throughout the sentence served and even after release.

Let us no longer have this traditional stance, rather should we try to embolden others to move on from their actions?

And can groundless nimbyism be finally assigned to history?

I am mindful that pain and grief still abounds, that some crimes will not be erased from our minds, and that crimes will stubbornly continue. But surely, the answer cannot be to condemn those who have done wrong to a lifetime without forgiveness.

To move forward as a society, we need to discourage the continual need to offer an apology, and instead accept when former prisoners have paid their dues and served their sentences. Only then will we move from a vicious cycle of unending penitence to a world in which reform and redemption is truly possible.

~

An edited version of this article was first published on 28 February 2022 by New Thinking.

~

IMB Soap Opera

Is the IMB like liquid soap?

Not the wonderful clear stuff which has a beautiful fragrance and an antibacterial effect on everything it touches.

No, not that.

More like that gawd awful stuff you find in greasy dispensers at motorway service station toilets, where hygiene means tick boxing inspection sheets on the back of the door. Its colour an insipid artificial pink like slime from old boiled sweets left too long in the sun, and its smell nauseous like cat sick.

But it is its opacity that irks me.

Designed to deliberately obfuscate, smother and shroud all that has any proximity to it, you never truly know whether it has any cleansing properties at all.

I neither like nor trust opaque liquid soap.

I happily tolerate the clear stuff, so long as it really is clear and totally free of nasty microbeads, creaming additives and fake foam.

It would have been far better for the IMB if it had been a bar of soap. At least you know where you are with a bar of soap. Visible, tangible, relatable, practical, and likeable. A bar of soap has these and many other qualities about it which reassures me of its fitness for purpose.

From the moment it is unwrapped and placed at the side of the sink, its very presence reassures you. Sitting there unblemished and ready to serve, a fresh bar of soap exudes a sense of personalised attentiveness and an unwillingness to be corrupted by falling into the wrong person’s hands.

I don’t think it is too much to ask that a bar of soap is fresh and that I am the first person to use it. There are some things that are unacceptable to pass around.

Even if we were to believe all they tell us then, at best, IMB would resemble a remnant of used soap, cracked and old. Once so full of purpose, now degraded in the hands of multiple ministers and permanent secretaries. Put on the side, its usefulness expended but its stubborn existence more a token gesture of monitoring rather than an effective part of the hygiene of the justice system.

It is an exhausted specimen of uselessness despite what its National Chair, Secretariat, Management Board would have you believe. They justify their own sense of importance with the sort of job roles that place them on a pedestal. But in reality it all just smacks of self aggrandizement; as they say in Texas – “Big hat, no cattle.”

Where once I bought into this whole parade, now I see it for the parody that it is. Where once I was pleased to serve, now I call out the servitude that the system enforces on those who work within it.

Where once I would write the annual reports, now I challenge the pointlessness of recording observations and making recommendations, an utterly futile exercise because there was never any intention by the Ministry of Justice to do anything about them.

A fresh bar of soap has an impressive versatility about it. It can give you clean hands, yes, but it can go a lot further than that. It can be carved, shaped and fashioned into an object of extraordinary beauty.

Some people serving their time in prison surprise me when they produce such intricate objects crafted from something as humble as a fresh bar of soap; an allegory of their own lives, in some cases I have known. Arguably a work of art to be admired and cherished.

Whereas an old, cracked bar of soap has no such versatility or value, and does not merit being kept.

If you can’t wash your hands with it, you should wash your hands of it.

In its present form, the IMB needs to be replaced.

~

Should inmates be given phones?

Offenders who maintain family ties are nearly 40% less likely to turn back to crime, according to the Ministry of Justice. With secure mobiles being rolled out in prisons we ask…

Should inmates be given phones?

This was a question posed to me back in November 2021 by Jenny Ackland, Senior Writer/Content Commissioner, Future for a “Real life debate” to be published in Woman’s Own January 10th 2022 edition.

Below is the complete article, my comments were cut down slightly, as there was a limited word count and reworked into the magazine style.

Communication is an essential element to all our lives, but when it comes to those incarcerated in our prisons, there is suddenly a blockage.

Why is communication limited?

It is no surprise that mobile phones can serve as a means of continuing criminal activity with the outside world, as a weapon of manipulation, a bargaining tool, a means of bullying or intimidation.

But what many forget is that prison removes an individual from society as they know it, with high brick walls and barbed wire separating them from loved ones, family, and friends.

There is a PIN phone system where prisoners can speak with a limited number of pre-approved and validated contacts, but these phones are on the landings, are shared by many, usually in demand at the same time and where confidentiality is non-existent. This is when friction can lead to disturbances, threats, and intimidation.

Some prisons (approx 66%) do have in-cell telephony, with prescribed numbers, monitored calls and with no in-coming calls.

Why do some have a problem with this?

We live in an age of technology, and even now phones are seen as rewarding those in prison.

If we believe that communication is a vital element in maintaining relationships, why is there such opposition for prisoners?

In HM Chief Inspector of prisons Annual report for 2020, 71% of women and 47% of men reported they had mental health issues.

Phones are used as a coping mechanism to the harsh regimes, can assist in reducing stress, allay anxiety and prevent depression.

Let’s not punish further those in prison, prison should be the loss of liberty.

Even within a prison environment parents want to be able to make an active contribution to their children’s lives. Limiting access to phones penalises children and in so doing punishes them for something they haven’t done. They are still parents.

Who watches the Watchdog?

The website for the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) states:

“Inside every prison, there is an Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) made up of members of the public from all walks of life doing an extraordinary job!

You’ll work as part of a team of IMB volunteers, who are the eyes and ears of the public, appointed by Ministers to perform a vital task: independent monitoring of prisons and places of immigration detention. It’s an opportunity to help make sure that prisoners are being treated fairly and given the opportunity and support to stop reoffending and rebuild their lives.”

Anyone can see this is a huge remit for a group of volunteers.

IMB’s about us page also states:

“Their role is to monitor the day-to-day life in their local prison or removal centre and ensure that prisoners and detainees are treated fairly and humanely”

Another huge remit.

For those who believe they can make a difference, and I have met a few who have, the joining process is quite lengthy.

Once you have completed the online application form, bearing in mind you can only apply to prisons which are running a recruiting campaign (that doesn’t mean to say there are no vacancies in others) the applicant is then invited for an interview and a tour of the prison.

So, what is wrong with that you may ask?

At this point NO security checks have been done, so literally anyone can get a tour of a prison, ask questions, and meet staff and prisoners.

This is surely a red flag.

And then there is the ‘interview’.

Two IMB members from the prison you have applied to and one from another prison take it turn in asking questions. It is basically a ‘tick box exercise’; I know this because I have been involved myself, sitting on both sides of the table.

It is based on scores, so if you are competent in interviews, you will do well. With IMB boards desperate for members it means that as long as your security check comes through as okay, you will have made it on to the IMB board.

However, no references are required to become a prison monitor. NONE.

A red flag too?

One of the main problems I encountered was that if the IMB board member comes from a managerial background they will want to manage. But the IMB role is about monitoring a prison and not managing it. I have seen where members and staff have clashed over this.

Well done, you made it on to the board, what next?

Back to the IMB website:

“You do not need any particular qualifications or experience, as we will provide all necessary training and support you need during a 12-month training and mentoring period”

The first year is the probationary year where you are mentored, accompanied, and trained. To be accompanied for this period is unrealistic, there are insufficient members having neither the time nor resources to get new members up to speed before they start monitoring.

In addition, induction training can be between 3-6 months after joining and can be said it is at best haphazard.

As reported Tuesday by Charles Hymas and others in The Telegraph newspaper, and citing a set-piece statement from the MOJ press office, “a spokesman said that although they had unrestricted access, they were given a comprehensive induction…”

I beg to differ; the induction for IMB board members is hardly comprehensive.

I believe this needs to change.

For such an essential role, basic training must take place before stepping into a prison. Yes, you can learn on the job but as we have seen recently, IMB members are not infallible.

Membership of the IMB is for up to 15 years which leads to culture of “we’ve always done it this way”, a phrase all too often heard, preventing new members from introducing fresh ideas.

What if something goes wrong?

Not all IMB members have a radio or even a whistle or any means of alerting others to a difficult situation or security risk. If for any reason you need support from the IMB Secretariat, don’t hold your breath.

The secretariat is composed of civil servants, MOJ employees, a fluctuating workforce, frequently with no monitoring experience themselves who offer little or no assistance. I know, I’ve been in that place of needing advice and support.

What support I received was pathetic. Even when I was required to attend an inquest in my capacity as a IMB board member no tangible help was provided and I was told that IMB’s so-called ‘care team’ had been disbanded.

From the moment you pick up your keys, you enter a prison environment that is unpredictable, volatile and changeable.

As we have seen this week, an IMB member at HMP Liverpool has been arrested and suspended after a police investigation where they were accused of smuggling drugs and phones into prison.

This is not surprising to me and may be the tip of the iceberg. IMB board members have unrestricted access to prisons and prisoners. As unpaid volunteers they are as susceptible to coercion as paid prison officers.

Radical change needs to be put in place to tighten up scrutiny of, and checks on, members of the IMB when they visit prisons either for their board meetings or their rota visits.

In 4 years of monitoring at HMP/YOI Hollesley Bay I was never searched, and neither was any bag I carried. In over 10 years of visiting prisons, I can count on one hand, with fingers to spare, the number of times I have been searched. When visiting a large scale prison such as HMP Berwyn I only had to show my driving licence and the barriers were opened.

Whilst the situation at HMP Liverpool is an ongoing investigation and whilst the outcome of the investigation is not yet known, I do urge Dame Anne Owers, the IMB’s national Chair, to look urgently at the IMB recruitment process, at the IMB training and at the provision of on-going support for IMB board members.

Complacency has no part in prisons monitoring.

~

Hidden Heroes: Why are they hidden and why are they heroes?

Today, 29 September 2021, is the second Hidden Heroes Day. An initiative of The Butler Trust it aims be “a National Day of Thanks for our #HiddenHeroes across the UK”. As well as Hidden Heroes Day, there is a dedicated website http://www.hiddenheroes.uk and social media account.

“While most media coverage of the sector focuses on the negative, the @HiddenHeroes_uk Twitter account is used to share positive stories about prisons, IRCs, probation and youth justice services, and the #HiddenHeroes who work in them.”

Why is it that our prisons, IRCs, probation, and youth justice services is apparently full of hidden heroes?

It is one thing calling them heroes, but why are they hidden?

Who has made them hidden and what is keeping them hidden?

Are they hiding and if so what from?

Are they hiding something or from something?

Are they hidden because they don’t want a fuss or hidden because they don’t want people to know?

In this day and age, why is the harsh reality of prisons so well hidden?

How can it be that the average person still knows so little about what is happening behind prison walls?

Direct experience

It has been more than 10 years since I first stepped into a prison. The unfamiliar surroundings can quickly intimidate and unsettle you, and the smell can be nauseating.

Back then, I had to hide my job role. Some of my thoughts on my way to do my monitoring rota at a prison once were: “I need to get petrol for the journey to work, so I had better put my belt and key chain in my bag this morning as I don’t think I am supposed to let anyone see it. No one has said anything, and I haven’t read any rules about it, but I’ve got a feeling that it should stay hidden until I get to the prison car park. That’s the thing about being a prison monitor, there seems to be so many unwritten rules and regulations.”

How many paid staff feel that they too must hide the job they do from others?

I remember visiting a high security prison, for an Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) tour of the prison. We walked together as a small group and headed into a workshop. It was an example of one of those mind-numbingly boring workshops found in nearly every prison where they perform so-called “purposeful activity”.

As we entered escorted by IMB volunteers I was told by a member of staff that within that large room there were two blind spots. In a hushed voice they said:

“We are not responsible for your safety if you walk into a blind spot.”

The problem was that they avoided telling us where the blind spots were, for fear of being overheard.

Is that what is meant by hidden?

Yes, it can be a dangerous for staff but so too for those living inside.

Prisoner-on-staff attacks are counted, and stats reported. And they should be. Prisoner-on-prisoner attacks are also counted, and stats reported and they should be too. But have you ever tried to get stats for staff-on-prisoner attacks?

Along with others, perhaps yourself included, I took the time to review the HM Chief Inspector of Prisons report in August 2021 on HMP Chelmsford. The report said:

“Almost half of the prisoners said they had been victimised by staff, and those with disabilities and mental health problems were significantly more negative.”

How can you call them hidden heroes when reading something like this?

Should that be hidden too?

Can those who do such things really be heroes?

Opinions differ

Whilst preparing this blog, I decided to ask people for their views on Hidden Heroes.

Dita Saliuka told me:

“Prison staff get the good coverage in the media most of the time anyway and the public praise them for ‘doing a difficult job’. It’s more the prisoners that are labelled all sorts whether they committed a horrendous crime or not people just say all sorts just because they are a prisoner. I hate the word ‘hidden heroes’ so much as PPO (Prison and Probation Ombudsman) and Inquest clearly state that most deaths are due to staff failures so how is that a heroic thing? It’s disrespectful to us families that have lost a loved one in prison due to their neglect, failures and staff abuse.”

Phil O’Brien, who has a 40-year career in the Prison system, told me:

“I think it’s an excellent initiative. It quite rightly concentrates on the positives. But sometimes doing the dirty stuff can be equally effective and necessary but can’t be ‘celebrated’ because it’s not as easy to explain, not as attractive or appealing.”

Tough at the top

We have probably all read in the media this past week that there is a new Secretary of State for Justice, Dominic Raab MP, appointed on 15 September in the reshuffle. But did you also see that he has been quite vocal on what he really thinks about prisons.

Mr. Raab has said: “We are not ashamed to say that prisons should be tough, unpleasant and uncomfortable places. That’s the point of them”

Compare that with the official line that Ministry of Justice takes: “We work to protect and advance the principles of justice. Our vision is to deliver a world-class justice system that works for everyone in society.” And, according to its 4 strategic priorities, “a prison and probation service that reforms offenders”

https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/ministry-of-justice/about

We are yet to learn the full extent of who is hiding what from whom at Petty France.

Mr. Raab will have to confront a few bastions of power there which prefer things to be properly hidden.

End of the day

#HiddenHeroesDay will come and go. Some people burst with enthusiasm for it, raising lots of money for great causes and all that is, of course, to be commended.

But at the end of the day the fact remains that the enduring problem of the criminal justice system, and daily for frontline workers in particular, is the pervading culture which dictates that everything remains hidden.

If we are to celebrate anything, wouldn’t it be better to celebrate openness rather than that which is hidden?

But within the justice arena so many tragedies stay hidden. Too many lives ruined, too many suicides, too many people suffering with mental health issues. And it is worsening by the day. That is the stark reality. And the reason things are hidden.

The Butler Trust, in creating the initiative, no doubt has the best of intentions.

In celebrating Hidden Heroes Day are we not in fact perpetuating the very problem it is trying to solve?

~ ends ~

Guest blog: Being visible: Phil O’Brien

An interview with Phil O’Brien by John O’Brien

Phil O’Brien started his prison officer training in January 1970. His first posting, at HMDC Kirklevington, in April 1970. In a forty-year career, he also served at HMP Brixton, HMP Wakefield, HMYOI Castington, HMP Full Sutton, HMRC Low Newton and HMP Frankland. He moved through the ranks and finished his public sector career as Head of Operations at Frankland. In 2006, he moved into the private sector, where he worked for two years at HMP Forest Bank before taking up consultancy roles at Harmondsworth IRC, HMP Addiewell and HMP Bronzefield, where he carried out investigations and advised on training issues. Phil retired in 2011. In September 2018, he published Can I Have a Word, Boss?, a memoir of his time in the prison service.

John O’Brien holds a doctorate in English literature from the University of Leeds, where he specialised in autobiography studies.

You deal in the first two chapters of the book with training. How do you reflect upon your training now, and how do you feel it prepared you for a career in the service?

I believe that the training I received set me up for any success I might have had. I never forgot the basics I was taught on that initial course. On one level, we’re talking about practical things like conducting searches, monitoring visits, keeping keys out of the sight of prisoners. On another level, we’re talking about the development of more subtle skills like observing patterns of behaviour and developing an intimate knowledge of the prisoners in your charge, that is, getting to know them so well that you can predict what they are going to do before they do it. Put simply, we were taught how best to protect the public, which includes both prisoners and staff. Those basics were a constant for me.

Tell me about the importance of the provision of education and training for prisoners. Your book seems to suggest that Low Newton was particularly successful in this regard.

Many prisoners lack basic skills in reading, writing and arithmetic. For anyone leaving the prison system, reading and writing are crucial in terms of functioning effectively in society, even if it’s only in order to access the benefits available on release.

At Low Newton, a largely juvenile population, the education side of the regime was championed by two governing governors, Mitch Egan and Mike Kirby. In addition, we had a well-resourced and extremely committed set of teachers. I was Head of Inmate Activities at Low Newton and therefore had direct responsibility for education.

The importance of education and training is twofold:

Firstly, it gives people skills and better fits them for release.

Secondly, a regime that fully engages prisoners leaves less time for the nonsense often associated with jails: bullying, drug-dealing, escaping.

To what extent do you believe that the requirements of security, control and justice can be kept in balance?

Security, control, and justice are crucial to the health of any prison. If you keep these factors in balance, afford them equal attention and respect, you can’t be accused of bias one way or the other.

Security refers to your duty to have measures in place that prevent escapes – your duty to protect the public.

Control refers to your duty to create and maintain a safe environment for all.

Justice is about treating people with respect and providing them with the opportunities to address their offending behaviour. You can keep them in balance. It’s one of the fundamentals of the job. But you have to maintain an objective and informed view of how these factors interact and overlap. It comes with experience.

What changed most about the prison service in your time?

One of the major changes was Fresh Start in 1987/88, which got rid of overtime and the Chief Officer rank. Fresh Start made prison governors more budget aware and responsible. It was implemented more effectively at some places than others, so it wasn’t without its wrinkles.

Another was the Woolf report, which looked at the causes of the Strangeways riot. The Woolf report concentrated on refurbishment, decent living and working conditions, and full regimes for prisoners with all activities starting and ending on time. It also sought to enlarge the Cat D estate, which would allow prisoners to work in outside industry prior to release. Unfortunately, the latter hasn’t yet come to pass sufficiently. It’s an opportunity missed.

What about in terms of security?

When drugs replaced snout and hooch as currency in the 1980s, my security priorities changed in order to meet the new threat. I had to develop ways of disrupting drug networks, both inside and outside prison, and to find ways to mitigate targeted subversion of staff by drug gangs.

In my later years, in the high security estate, there was a real fear and expectation of organised criminals breaking into jails to affect someone’s escape, so we had to organise anti-helicopter defences.

The twenty-first century also brought a changed, and probably increased, threat of terrorism, which itself introduced new security challenges.

You worked in prisons of different categories. What differences and similarities did you find in terms of management in these different environments?

Right from becoming a senior officer, a first line manager at Wakefield, I adopted a modus operandi I never changed. I called it ‘managing by walking about’. It was about talking and listening, making sure I was there for staff when things got difficult. It’s crucial for a manager to be visible to prisoners and staff on a daily basis. It shows intent and respect.